Writing Breathing the Night Out didn’t just help me heal; it brought everything into focus. It revealed the uncomfortable truth about the women in my childhood and the ways they enabled child sexual violence.

The Hidden Scale of Child Sexual Violence in Canada

In Canada it is estimated that 1 in 3 girls and 1 in 5 boys face child sexual violence (CSV) — though recent survey data suggests the true numbers are complex and underreported.

What Police Data Really Shows

Let’s ask the front-line responders, the cops: CSV in Canada is widespread. Police-reported data shows that children under 18 make up over 60% of all sexual assault victims.

A National Trauma We Don’t Acknowledge

That’s more than 10 million people in this country living with trauma like mine. In a nation of just over 40 million, that means one-quarter of our population is navigating adulthood under the shadow of CSV. And that’s only counting the reported cases. The underreported and unreported cases push the number even higher.

Putting the Numbers in Perspective

To put it in perspective: that’s the equivalent of every resident of Ontario and Quebec combined. The number of Canadians who have experienced CSV far exceeds the number of police-reported domestic violence cases each year. Imagine it: CSV impacts more people than all Canadians who report being victims of property crime annually.

Where Is the Media Coverage?

How often do we watch the 6 o’clock news and hear about property crime? Home invasions are a “hot topic.” Where is the CSV crime report? Not the names, just the numbers. Where are those reports in the media? Is it because it’s too uncomfortable a topic to discuss on TV? Will someone get offended if we start flinging these stats in their face? Something to think about.

When Do We Call It a National Crisis?

So here’s the question we need to ask: what number do we need to reach before child sexual violence is considered a national crisis?

The Gender Imbalance We Must Acknowledge

With numbers that staggering, you might expect far more female sexual predators. But there’s a catch: women and girls are overwhelmingly targeted by men. When you understand that imbalance, the picture shifts. Most women aren’t the ones committing the violence — they’re the ones being harmed.

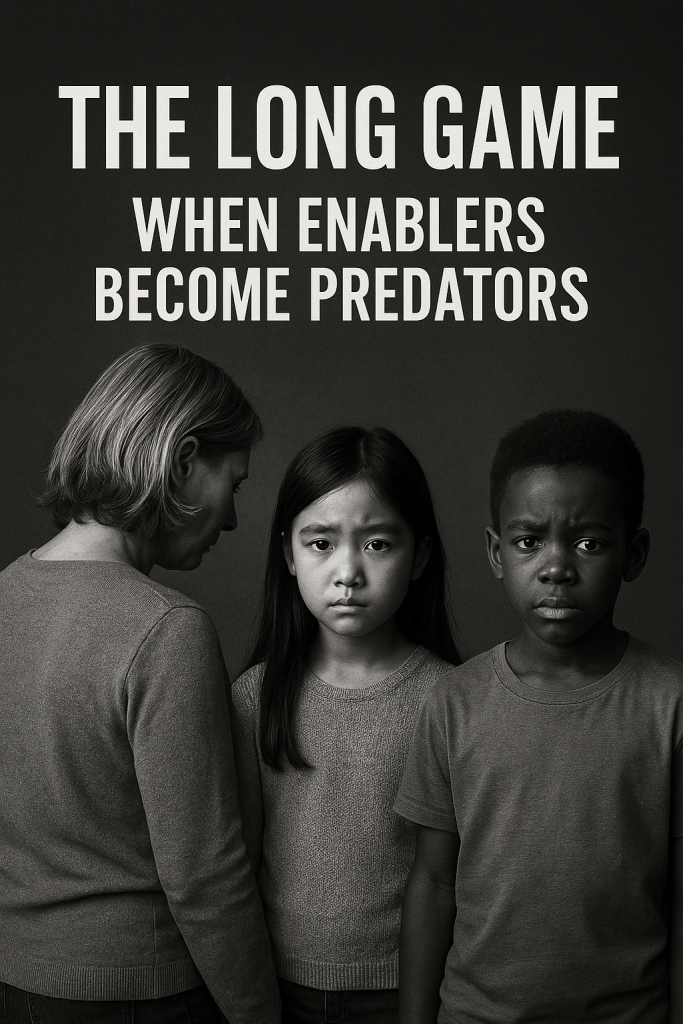

The Uncomfortable Truth About Enabling

But here’s the uncomfortable truth we seldom talk about: women can become predators in another way. The long game kind. The enabler kind.

My Lived Reality

I’ve lived this.

No woman ever infused me with CSV, but many women turned their backs. They minimised, denied, avoided, or pretended not to see. And that silence — that “not my business,” or “this happens in all families,” or “you brought this upon yourself” — gave the predators in my life the space they needed.

The Deeper Wound: Betrayal by Those Meant to Protect

In many ways, the women who refused to act hurt me more deeply than the men who committed the violence.

Because I needed them. I needed protection. I needed someone to believe me. I needed one adult — just one — to say, “Enough.” None did.

The Echo in Adulthood

And that betrayal echoes into adulthood. The CSV ended decades ago, but the crazy-making, the denial, the rewriting of history, and the quiet punishments continue. Being disinvited from family gatherings — like salt rubbed into a wound they refuse to acknowledge — is its own form of violence. They go out of their way to ensure I know I’m not welcome. The “just get over it” mindset doesn’t fade with time. It follows me. Daily.

What Do We Call an Enabler?

We don’t like to label enablers as predators. But what else do you call someone who knowingly gives a predator access to a child? Who puts comfort above a child’s safety? Who defends a man’s reputation instead of a child’s well-being?

They are predators with clean hands.

Predators who never touch, but still destroy.

What the Research Tells Us

A Canadian study by the Correctional Service of Canada found that 80% of men and 86% of women in federal prison reported at least one adverse childhood experience (ACE).

Another Canadian study, carried out in a federal penitentiary in Québec, identified four distinct “trajectories” of childhood adversity among people convicted of sexual crimes — including a “poly-victimisation (multiple types of trauma, sexual, physical, neglect etc.)” path that links early exposure to trauma with substance use, violence history, and high-risk behaviours later on.

Trauma Is More Than a Single Event

But trauma isn’t only sexual. Trauma is neglect. Abandonment. Being unseen. Sacrificed to preserve family peace. Being told your truth doesn’t count.

How Trauma Turns Women into Enablers

When women — mothers, grandmothers, aunts, sisters — carry unhealed trauma, they can become enablers. Not always out of malice, but because they’re replaying patterns they never escaped. Because denial is safer than reality. Because silence is what their childhood taught them.

Good Intentions Do Not Erase Harm

But good intentions don’t erase the harm.

A predator needs access.

An enabler provides it.

Different roles, same outcome.

The Destruction of the Long Game

The long game of enabling is slower, quieter, and harder to name — but just as destructive. Sometimes more so.

When the people who are supposed to protect you choose not to, the wound doesn’t end with you. It becomes intergenerational. It becomes cellular. That is where trauma lives.

Trauma isn’t the event itself — it is the unresolved memory of what happened (CSV) or what should have happened (protection). Trauma is a wound that keeps seeping. And when it is left untreated or unacknowledged, it doesn’t just stay in the mind; it moves into the body.

Without healing, trauma can manifest as disease or mental health conditions. It can evolve into chronic illness, or into disorders like C-PTSD (Complex Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder). Trauma is not a moment in time — it is the echo of abandonment, carried forward until someone finally chooses to turn toward it and heal.

If We Want to Stop Predators, We Must Stop Enablers

If we ever hope to stop the next generation of predators — those who spring from pain, chaos, neglect, and silence — we have to face this: stopping child sexual violence isn’t just about stopping the offenders. It’s about stopping the enablers, especially those who don’t see themselves as part of the harm.

Here’s another reality we need to put on the table of awareness: A predator can only reach a child when they have access — and that is where the enabler steps in. They open the door. They assist. A predator may harm once. But an enabler, by granting access again and again, effectively assists multiple predators.

This is why enablers often commit the greater crime: they become the organised, conditioned conduit that matches a helpless child with a hungry predator.

This Isn’t About Blame — It’s About Truth

I’m not writing this to blame all women.

I’m writing this because this is my truth. And the truth of many of us who survived CSV but never felt safe enough to say it.

This isn’t about gender.

It’s about accountability.

About breaking cycles instead of repeating them.

About understanding that doing nothing is not neutral.

Doing nothing is something.

Predators destroy bodies.

Enablers destroy trust.

Both leave scars.

And when you’ve lived through both, you learn:

The long game can be just as deadly.

The Original War

This is the original war — the war against children.

This Is Important

Not everyone who suffers child sexual violence grows up to become a predator or an enabler. And enablers are not only women — men can be enablers too. It is a choice. The more we educate ourselves, the more we drag CSV out of the shadows. The stronger the light becomes — and light is love. Awareness, exposure, and action are what weaken child sexual violence. Together, we can break the cycle.

Call to Action

It’s time to recognise it. Speak up. Protect. Heal.

Together, we heal. Together, we fight to end child sexual violence.

References

Correctional Service Canada. (2023). Adverse childhood experiences and federal offenders: A research report (Report No. 445). Government of Canada. https://www.canada.ca/en/correctional-service/corporate/library/research/report/445.html

van den Berg, J., de Vogel, V., & van Marle, H. (2023). Adverse childhood experience trajectories and high-risk behaviors among sexual offenders: A Canadian federal penitentiary study. PubMed Central. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37725879/

Astridge, H., Li, S., McDermott, D., & Longhitano, M. (2023). Adverse childhood experiences and youth reoffending: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry, 23, Article 147. https://bmcpsychiatry.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12888-016-1001-8

Baumer, E., Jackson, A., & Smith, L. (2022). Adverse childhood experiences, aggression, and psychopathology in adult males accused of rape. PubMed Central. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36157007/

Millennium Cohort Study. (2023). Adverse childhood experiences and adolescent delinquency: Evidence from the UK. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(4), 3202. https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/20/4/3202