Originally Published: Oct 31 2025

What Do Pocahontas and Pretty Woman have in Common? They were both females caught in systems that treated them as property, not people. They were sex slaves fighting to survive a rape culture.

To force anyone into sexual slavery, you must first dehumanize them — strip away rights, dignity, and identity. Once that’s done, they’re no longer seen as human; they’re an object to be used.

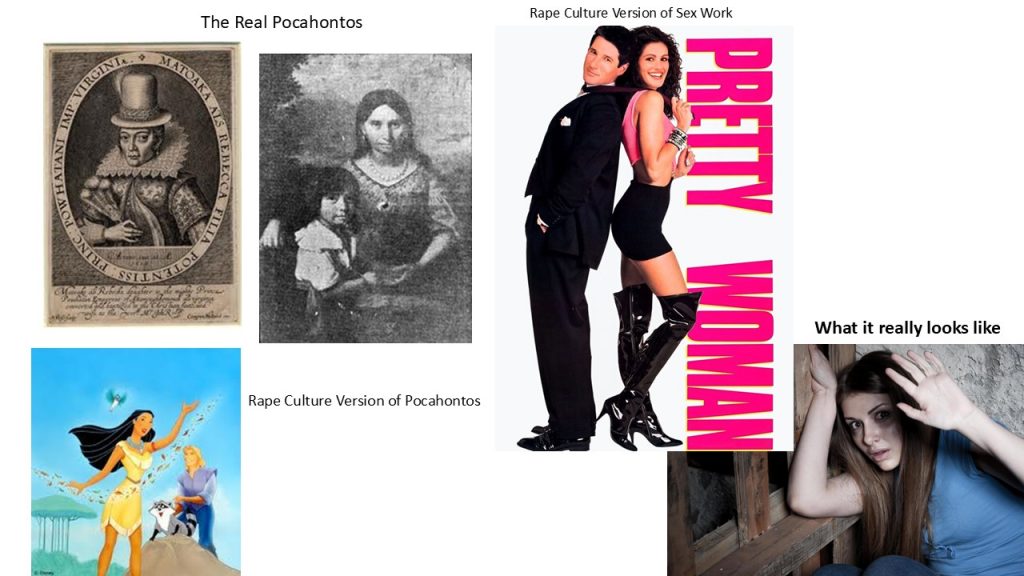

Let’s start with Pocahontas, check out the photo with this article.

In order to understand how 12-year-old Pocahontas was forced into sexual servitude under colonial domination, it helps to first examine what I call the Disney Spell.

Jack Zipes, in Breaking the Disney Spell, argues that Walt Disney capitalized on American innocence and utopianism to reinforce the social and political status quo. Zipes’ assessment of Disney is accurate — Disney did cast a spell on America.

During the 1930s, Disney recognized a country’s vulnerability and its desperate need for distraction. He offered the public escapism as a way to revitalize the economy. This formula — a blend of consumerism, escapism, and sexism — became the foundation of the Disney empire.

To mass-market the 1995 film Pocahontas, Disney took the story of a legendary and courageous Indigenous woman and reduced her into a mischievous, sexualized fairy-tale creation.

Walt Disney was born in 1901 and began his career as an animator in 1922, at the peak of Henry Ford’s Model T mass production.

Fordism, a term derived from Frederick Taylor’s work, simplified manufacturing and introduced higher wages for workers, creating the first large-scale consumer class in modern history. Millions of vehicles were produced at lower costs, allowing working-class people to participate in consumer culture for the first time. Ford capitalised on this by building amusement parks and museums—destinations where families could drive in their new cars on their scheduled days off. It was a brilliant cycle of profit: Ford paid his workers enough to become his own best customers. This new culture of consumption directly inspired Disney, and consumerism became the first ingredient in his formula.

During the 1920s, escapism for the working class meant temporary relief from factory life — dance halls, sports, or movie theatres. But during the Great Depression (1929–1939), escapism became essential. Movie theatres acted as community centres, offering hope to the jobless and hungry.

Disney tapped into this anxiety, creating The Three Little Pigs (1933) and Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937) — films that reflected the nation’s despair and promised salvation through optimism. These stories presented helpless, poor victims (the pigs, Snow White) pursued by villains representing wealth and authority (the wolf, the evil queen), only to be saved by a hero. The message reinforced the “American Dream”: paradise is available to all who wait.

Disney capitalized on this sentiment, building immense wealth as most Americans struggled to survive. Escapism became the second ingredient in his formula.

Walt Disney died in 1966, but his name and formula became corporate legend. By the 1990s, profits depended on intensifying audience engagement. In a culture marked by growing anti-feminist backlash, Disney executives added a third ingredient — heightened sexuality.

Femininity has always been a social construction shaped by cultural context. In Pocahontas, the foundational subtext aligns with Charles Perrault’s 17th-century views on women — that they are valued for beauty, submission, and virginal purity, and that being chosen by a male hero is the ultimate reward.

This narrative reinforces what feminist scholars identify as rape culture — a society that normalizes sexual violence, blames victims, and rewards submissive femininity. Rape culture holds that if a woman, or a girl, is violated, she somehow “allowed” it by failing to be passive or pure enough.

A short educational clip titled What is Rape Culture? explains how media and institutions perpetuate these beliefs, teaching audiences — even children — to internalize gendered blame.

Disney’s Pocahontas exemplifies this. While the film portrays the hero, John Smith, as the object of Pocahontas’s affection, its subtext sexualizes her image and distorts her real story. By the 1990s, Disney was marketing directly to young girls using overt sexual imagery.

Compare Snow White’s floor-length gown, which concealed her body, with 12-year-old Pocahontas’s one-shoulder mini-dress that barely covers her crotch and oversized breasts. The latter’s presentation — bold, flirtatious, and rebellious — mirrored the anti-feminist shift of the 1990s, when music, fashion, and film commodified women’s bodies under the guise of “empowerment.”

Disney’s marketing taught girls that desirability equated to freedom — that long hair, a slim body, and sexual appeal could attract love and rescue. Even though Pocahontas was more assertive than Snow White, she was reduced to a sexual symbol and sold as such to a generation of children.

In reality, Pocahontas was not a fictional character but a historical figure with a powerful story.

Pocahontas, daughter of Chief Powhatan of the Algonquian nation, was born around 1595 in Chesapeake, Virginia. She was 12-years-old when she first encountered John Smith, who had been captured by her people after killing two warriors.

According to Algonquian tradition, both men and women could decide the fate of captives, reflecting gender equality in their culture. As the chief’s daughter, Pocahontas had authority to claim Smith and was responsible for his survival — which she ensured by providing food during “The Starving Time.”

However, one of her visits to the ship where Smith lived ended in betrayal. The English captured Pocahontas and held her hostage. During her captivity, she was taught English, converted to Christianity, and renamed Rebecca. Letters later uncovered by the Smithsonian show that John Smith described their connection as a “love story.”

Pocahontas was a child, kidnapped and confined, with no freedom to consent. To describe such a relationship as romantic is to erase the violence inherent in it.

For nine years, Pocahontas endured captivity and exploitation, surviving by adapting to the roles imposed on her. She became a mediator between the Powhatan and the English — a political role that required intelligence, diplomacy, and emotional resilience.

At age 21, she married John Rolfe, a tobacco farmer, as part of a broader colonial effort to “civilize” Indigenous people through assimilation. Shortly after, she was taken to England as proof of that project’s success.

There, she commissioned a portrait dressed in masculine attire — a stiff collar and tall hat — asserting her intellect and political status, presented in the photo. Another portrait, depicting her with her son Thomas Rolfe, was painted before her death in 1617, at just 22-years-old.

Here’s a short clip that explains how Pocahontas became a sex slave Everything Pocahontas Told Me Was A Lie.

Throughout her brief but extraordinary life, Pocahontas demonstrated strength, intelligence, and compassion. She sought peace between her people and their colonizers — even as she was used as a sex slave, hunter, chef, translator and negotiator.

This true story should have inspired portrayals of female leadership and resilience. Instead, as Jack Zipes argued, Disney’s “spell” transformed it into a sanitized, sexualized product — one that perpetuated consumerism, escapism, and sexism at the expense of truth.

When an entire empire profits from turning a child’s suffering into a romantic story, it’s not just poor storytelling — it’s child sexual exploitation and a crime against humanity.

The historical record is clear: Pocahontas was a child forced into captivity and exploited by a colonial power. That’s not love. That’s coercion — and that, by every moral standard, is sex slavery.

Further deconstructing Disney’s film Pocahontas’s sub-text and imagery combined reconfirmed the feminine code to perform, which is how a society, aka Rape Culture, expects a female to behave.

Let’s stop there for a moment.

This is not the first time a pedophile has called a relationship with a 12-year-old kidnapped, confined, and raped a “loving relationship.” For nine years, Pocahontas did the only thing she could: she survived. She navigated captivity by appearing compliant, performing the role expected of her, and finding ways to be useful beyond being forced into sex slavery, hunting, and cooking. White Christian society praised this as Pocahontas being a “good Indian.”

But let’s be clear: all the commentary and spin doesn’t change the fact that when an adult — or, in this case, an entire military operation — kidnaps and sexually exploits a 12-year-old, whether for one day or nine years, it is sex slavery.

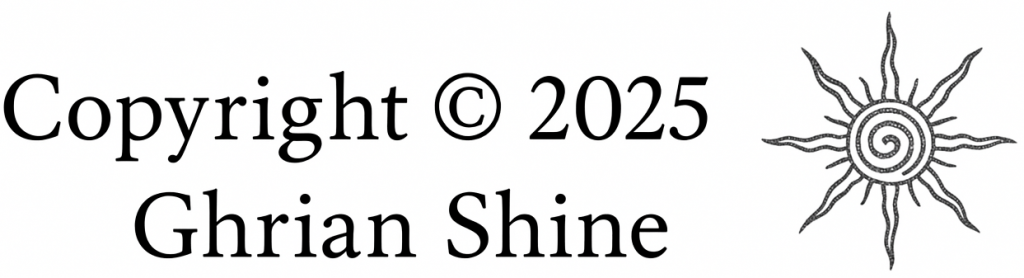

Pretty Woman you’re up next, see the photos. The 1990 box-office hit, started as a dark story about the reality of the sex slave industry — before Disney got involved. Here’s a short clip that explains how Julia Roberts got tricked into doing the movie: Julia Roberts: Pretty Woman was a Dark Screenplay.

Former sex worker Marian Hatcher told Time the movie was ridiculous. She said she’s never met a sex worker whose life turned out even remotely like Vivian’s. In the film, Vivian meets a cute client (Richard Gere), eats strawberries, goes on a shopping spree, and ends up with a rich, charming guy who buys her necklaces and takes her to the opera — happy ever after.

Hatcher, now an advocate for sex workers, insists the real world doesn’t work that way. Women in the industry are often kidnapped, imprisoned, beaten, and raped repeatedly. When they’re “released,” they aren’t free, they are now just not chained to a bed. They are put on the streets selling sex, constantly monitored — just like a herd of cattle. The women fear their captors more than their clients. That is sex slavery. Vivian’s story doesn’t show that — but the real-life Julia Roberts signed up thinking it might.

Pretty Woman has been cited again and again as glamorizing sex work and selling a “Cinderella” rescue fantasy — there’s Disney again. Scholars and journalists — like Dalla (Exposing the ‘Pretty Woman’ Myth), Hodgson (The Guardian), and TIME’s Here’s What Former Sex Workers Think of Pretty Woman — argue the film romanticized sex work, making it seem glamorous, voluntary, and upwardly mobile.

These myths reshaped public imagination, influencing young women to migrate to Los Angeles and chase sex work instead of movie stardom, believing a Prince Charming would rescue them. That is rape culture in action.

Where the heck did rape culture begin? Rape culture thrives on contradiction—it keeps women trapped by demanding the impossible, then blaming them for failing to achieve it. Rape culture didn’t just show up one day. It was built—brick by brick—by people who needed to control bodies they didn’t own. White Christians used sexual violence against children as a way to break spirits and secure power. Over time, that control got dressed up as morality, tradition, even “protection.” But underneath it all, it’s the same thing: domination, ownership, and profit. What started as control through fear became an industry that feeds off silence and shame.

I learned more about Rape Culture in my social justice classes, especially Indigenous studies. Roman Catholic Jesuit Priests came to Canada in 1540. By 1632, Paul Le Jeune wrote back to France: “They treat their children with wonderful affection, yet preserve no discipline, for they neither themselves correct them nor allow others to do so.” Ten years later, he added that “correction” was being applied — slowly, with “good effect.”

In 1828, the first residential school in North America opened in Brantford, Ontario, Canada — the Mohawk Institute. By law, Indigenous kids were ripped from their parents. For 168 years, Christian-run schools under government orders worked to “kill the Indian in the child.” That wasn’t poetic — it was the mission. The authorities believed if they could “fix” these kids, the problem would disappear.

Where did the priests learn this? From the Doctrine of Discovery — first issued by the Pope in 1452, again in 1493. It told European colonizers how and why to subjugate “new” peoples. Watch What is the Doctrine of Discovery? | NDN POV | TVO Today for the full breakdown — and try a little experiment: remove the word “Indigenous” whenever they talk about how these people were treated.

Here’s the truth: this wasn’t only about Indigenous children. White Christians were taught this for over 2,000 years — that children could be beaten, starved, raped, and controlled — and that it was their right. Hurt people hurt people.

This is the original war — a war on our children. Control the kids, and you control the parents. Control the parents, and you control the world. All so a few fat cats can line their pockets off our backs. Greed. Addiction. A machine that devours everything and is never satisfied.

We don’t have to live in a rape culture.

We can help each other heal — but first, we have to understand how we got here. How else will we find a new way?

Together, we heal. Together, through love and justice, we can end child sexual violence.

References

Bio.com. ‘Walt Disney Biography’. A&E Television Networks. http://www.biography.com/people/walt-disney-9275533?page=2. Retrieved June 4, 2012

Butsch, Richard. The Making of American Audiences. http://www.blackwellpublishing.com/content/BPL_Images/Content_store/Sample_chapter/9780631219590/001.pdf

Dalla, R. L. (2000). Exposing the “Pretty Woman” myth: A qualitative examination of the lives of female streetwalking prostitutes. University of Nebraska–Lincoln, DigitalCommons.

Hodgson, N. (2015, March 23). Pretty Woman still successfully hawks the Cinderella fantasy after 25 years. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/film/2015/mar/23/pretty-woman-25-years-cinderella-fantasy

Kidwell, Clara Sue. ‘Indian Women as Cultural Mediators’ The American Society for Ethnohistory [0014-1801] Vol. 39 Issue 2, p99 – 101. Retrieved from database: America: History and Life. 1992

Padurano, Dominique. ‘“Isn’t That a Dude?”: Using Images to Teach Gender and Ethnic Diversity in the U.S. History Classroom – Pocahontas: A Case Study’. History Teacher, Feb2011, Vol. 44 Issue 2, p191-208, 18p; Historical Period: 1616 to 2010. 2011

Pocahontas 1995 film. Disney Website. http://disney.go.com/disneyinsider/history/movies/pocahontas. Retrieved June 4, 2012

Smithsonian Magazine. Website. The True Story of Pocahontas is More Complicated Than You Might Think. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/true-story-pocahontas-more-complicated-than-you-might-think-180962649/ Retrieved February 20, 2024

Tatar, Maria. The Classic Fairy Tales. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc. 1999

Thompson, Fred. ‘Fordism, Post-Fordism and The Flexible System of Production’. Salem, Oregon: Willamette University http://www.willamette.edu/~fthompso/MgmtCon/Fordism_&_Postfordism.html. Retrieved June 4, 2012

TIME Staff. (2015, March 24). Here’s What Former Sex Workers Think of Pretty Woman. TIME Magazine. https://time.com/3752144/pretty-woman-sex-workers/

WGBH. (2013, November 19). Pretty Woman vs. the real world of prostitution. Public Broadcasting Service (PBS). https://www.wgbh.org/news/2013/11/19/pretty-woman-vs-real-world-prostitution